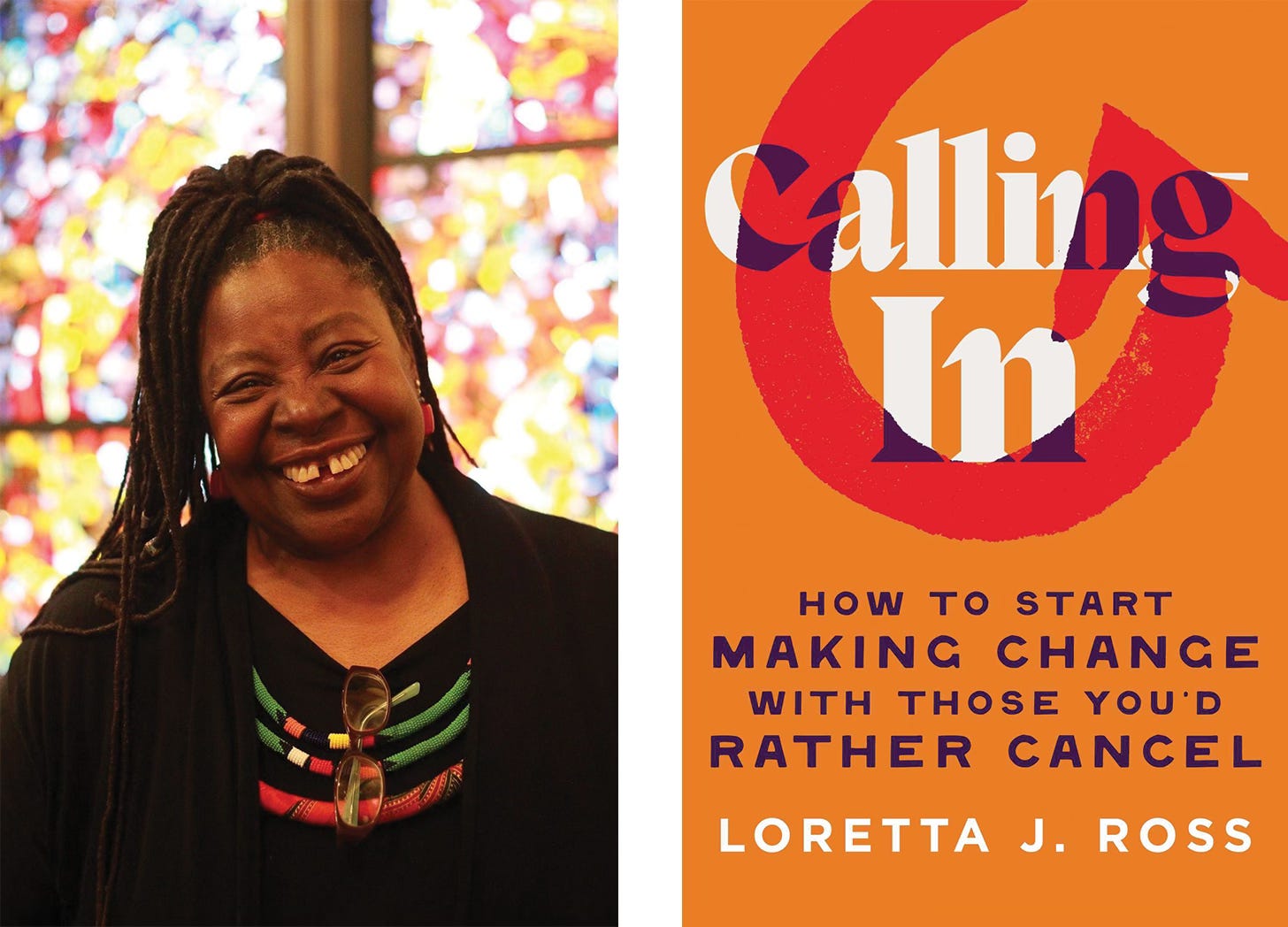

A powerful book to start off 2025 with

On Calling In: How to Start Making Change with Those You'd Rather Cancel

People opposed to human rights—opposed to ending poverty, addressing racism, or accepting women’s rights to control their bodies—think they’re fighting the human rights movement, but I believe they’re wrong. They’re fighting truth, history, and evidence. Most importantly, they’re fighting time. These existential forces are beyond their power to command. With truth, history, evidence, and time on our side, we hold the winning hand despite our fears of powerlessness and failure. Our opponents are simply pimples on the ass of time. But my biggest fear is that despite our winning hand, we’ll be defeated—at least in our lifetime—because we can’t stop calling each other out.

Loretta Ross

This quote is from the prologue of Calling In: How to Start Making Change With Those You’d Rather Cancel, from activist Loretta Ross. She’s referring to the left’s habit to turn on each other and focus on our differences instead of the values and goals we have in common. The results are anemic movements and a culture in which we don’t allow each other to grow and learn. In other words, Ross believes that call-out culture is keeping progressives from making progress, and I’m inclined to agree.

Calling In, which comes out Feb 4 from Simon and Schuster, is a manifesto and guide to how to create a culture of calling in, a term coined by trans writer and activist Ngọc Loan Trần in a 2013 BGD article. A call in, as Ross defines it, is “a call out done with love.”

It’s engaging with people who think differently than you using compassion and curiosity instead of anger and judgment.

I’ve been guilty of responding with anger when I knew it wouldn’t help the situation. And I’ve seen plenty of my friends do this when I know they’re otherwise caring people. The practice of calling in ought to be a part of any spiritual activist’s toolbox who holds values like modeling love and working toward humanity’s collective liberation.

Calling in isn’t about sweeping our differences under the rug or enabling poor behavior. It’s about creating what Ross refers to as “accountability culture.” Here’s what it looks like:

It’s not about feeling sorry for wrongdoers but about recognizing their humanity, in the same way we protect the humanity of victims. It’s about engaging in constructive—not destructive—conflict with each other. It’s about learning together to be less judgmental, more generous, more collaborative, and more appreciative of nuance and ambiguity. Do we want to silence those who make us think differently about things? Or do we want to engage in conversations that can hold multiple truths at the same time? We can hold people accountable using love, forgiveness, and respect, giving people room to grow—because they may be capable of changing. We can say what we mean and mean what we say, but we don’t have to say it mean. That’s a choice.

Ross’s wisdom has been hard-earned. She is a rape survivor who raised a child born of incest on her own. She’s also a survivor of sterilization abuse at age 23. She used her experiences to become one of the first black women to direct a rape crisis center and co-create the theory of Reproductive Justice. She’s a cofounder of the National Center for Human Rights Education and the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. The list of initiatives and organizations that she has led or assisted with is long and awe-inspiring.

The practice of calling in ought to be a part of any spiritual activist’s toolbox who holds values like modeling love and working toward humanity’s collective liberation.

Her new book comes from decades of experience in creating movements. She offers practical guidance about how to practice calling in, as well as when a call-out is justified.

What follows are a few key insights from the book.

Start with people who share 50% or more of your values

Within her many roles, Ross has worked with individuals that she would’ve preferred to abandon, including incarcerated rapists and murderers who wanted to change, and a reformed leader of the white supremacy movement. She’s helped people that no-one had any hope could change.

And reading about her experiences has given me hope at a time in which an attitude of “us vs them” feels not only justified but also necessary. But when I maintain a binary attitude, I betray my belief in everyone’s innate worth and humanity and my desire for an inclusive, beloved community. I’m not ready to abandon half the country, but I also recognize you can’t help people who don’t want to change, and most people who would consider themselves conservatives are not interested.

Despite Ross’s own experiences with some of the most extreme opponents out there, her advice on calling in is to start with folks who already share 50% or more of your values. These are the people who probably want to be our allies, even when it doesn’t always feel like they do.

“They may not know our keywords,” Ross writes. “They may be repelled by jargon that sounds elitist or half-Martian, but they share a sufficiently common worldview, one that values civic engagement, democracy, fairness, community service, justice, and leading by respecting others.”

The work, then, is how to build and maintain relationships and movements with people who share many of our values but still don’t always agree with us. This requires specific skills, such as the ability to stay compassionate in the midst of discomfort and a different vision for handling wrongdoings that allow for amends.

Calling in requires us to build up our tolerance to discomfort

Here’s the hardest part for me:

Calling in is not a better way to tell someone they are wrong. Its purpose is to create the conditions for differences of opinion to be heard, to allow facts to be ascertained, and to avoid ideological rigidity and political bullying. Its purpose is to prepare us to have difficult conversations—with our families, our classmates, our colleagues, our neighbors, and our friends.

I imagine this is the hardest part for most of us: allowing for differences of opinion. Especially when we can see how these differences of opinion may lead to harm. But the other extreme is just as bad, when critical thinking is discouraged, even outlawed:

When people have different ideas but move in the same direction, that’s a movement. When many people have the same idea and move in the same direction, that’s a cult. We are not building the human rights cult but the human rights movement.

I’ve had so many conversations with friends or family that, if I shared with other progressives, might’ve gotten me cancelled. Questioning so-called truths of leftist ideology. This is sad and frustrating. I want people to feel comfortable asking questions and critiquing commonly held beliefs. Doubting is what freed me from so much toxic theology and mainstream culture in the first place, like questioning how society was telling me to view my plus-sized body, my sexuality, or what it means to be a good person. I don’t want any of us to be afraid to question things, because that’s how we grow.

Ross recommends we start practicing calling in with folks who are already in our “sphere of influence.” These are our friends, family, coworkers, and community members with whom we’ve already established relationships. She quotes adrienne maree brown, who explained that change can only move at the “speed of trust.”

BTW, it’s a lot easier to have compassionate conversations in person. If you’ve ever tried calling in someone via a Facebook post, I think you’ll agree it’s really challenging. And it often comes across as a callout anyway.

Callouts can be justified

Callouts, meaning public critiques of someone or an organization’s actions or positions, are sometimes justified.

Ross has a whole list of times when it’s time to call out, not call in, such as “when serious harm or wrongs have been committed and when confronting a major power disparity.”

But we warned: once you call someone out, it’s hard to come back from that. Often, a bridge is burned or trust is damaged. And they don’t often lead to positive transformation.

“Call outs work when you know someone will never become an ally,” Ross explains. “But if there is a potential to start or deepen a relationship, give calling in a try instead.”

Check your motivation

Ross also encourages readers to check their motivation before calling out. Check whether your motivation is about power or change. Does it come from a place of anger or hope? When Ross started her activist career, she was driven by anger: “All those years, when I was acting out of unfocused anger, I’ve realized I was mostly just venting. I could make excuses and tie a bow on it … but ultimately I was acting out to make myself feel better, rather than to make my world better.”

Like Lama Rod Owens, Ross came to realize that her anger wasn’t useful until she “faced the pain underneath.” Once she did that, she was able to make more progress in building movements: she learned how to lead with love.

Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.

Martin Luther King, Jr

“I’ve found that my unavoidable negative emotions—anger, pain, anxiety—can best be countered by love,” she writes. “As Martin Luther King Jr. said, ‘Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.’”

Ross now uses King’s words as her North Star.

Check out Calling In for inspiration and practical advice about how to create a call in culture within your family, at work, in academic settings, and more. It’s a useful book for anyone who is organizing or leading any group, from a classroom to a nonprofit to a family reunion.

Note: this post contains affiliate links. Buying from these links is a way to support this project, the authors, and your local bookstore!