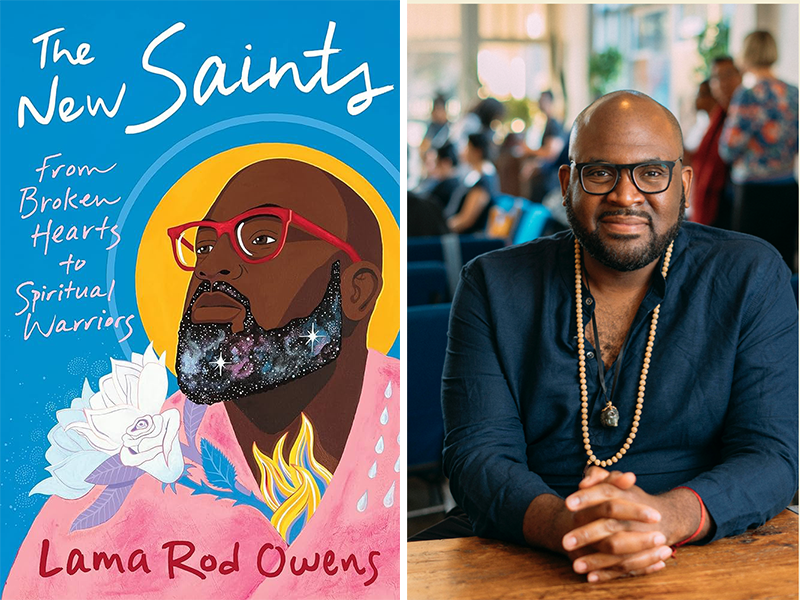

Buddhist teacher Lama Rod Owens is calling for a new era of spiritual activists he has labeled new saints. And new saints are not good people.

Or, more to the point, they’re not concerned with being perceived as good people. In his newest book The New Saints: From Broken Hearts to Spiritual Warriors, Owens explains that many of us learn to be good people for the wrong reasons:

So many of us are obsessed with being good because the performance and pursuit of goodness are tied to many cultural and religious ideas of being a person or human. If we are not good, we are not considered human. If we are not human, we are considered bad, flawed, or invalid, which means that we lose our humanity and become othered. In this otherness, we no longer receive the basic care that good people get.

Performing culturally acceptable versions of goodness is tied to “one of the most violent expressions of care: conditional love” and can even become a matter of survival.

Queer kids that are taught that it’s unacceptable to be gay stay in the closet when losing their families’ support could mean losing shelter and safety. Black Americans are taught not to act out since a run in with the police could mean their death. People in corporate jobs don’t speak out about sexism or ablism in their work environments since it could mean losing their ability to pay rent.

The ideas we have of what it means to be a good person have been manipulated and warped by systems of power and the dominant culture. For instance, Owens’ own education on goodness was “mostly informed by anti-Blackness, anti-queerness, ableism, class, and capitalism.” So was mine. I imagine yours was too, in one way or another.

As a result, we can’t disrupt the system if we’re still trying to follow societal rules of goodness or be perceived as a good person. In other words, learning to do good as opposed to perform goodness is all about checking your motivations:

We practice goodness not because we want to be seen as good or because we want to experience happiness or even because it is what we are supposed to be doing. We choose goodness because it’s how we get free while inviting others to join us.

True goodness, stripped of toxic influences, causes trouble which Owens defines as “creating discomfort for others.” True goodness doesn’t just disrupt systems of power, it disrupts our sense of the world and our sense of ourselves.

To practice this disruptive goodness requires redefining what goodness is, which also requires redefining what it means to be free.

And I have some bad news for those of us who are already actively trying to disrupt systems of power. Practicing goodness doesn’t mean following the progressive agenda.

Voting, educating ourselves, highlighting the voices of the most underrepresented folks, reading the current justice books … supporting charities, avoiding cracks and walking under ladders, and offering thoughts and prayers are all wonderful things to do, but they are more about feeling good about ourselves and making sure others view us favorably. Which of these beloved labors will actually get us free? (emphasis mine)

So many of us are exhausted and discouraged by the lack of change in this country and around the world. Fighting the same fights over and over again. Changing a law that gets overturned a few years later. Calling for a peace fire that doesn’t last. We have to ask: what does true freedom look like? And, more importantly, who gets to define it and for whom?

Owens defines freedom as “the agency to choose how we want to be in relationship with ourselves and the world around us.” And he splits this up into outer, inner, and secret freedom.

Outer freedom is “having access to all the resources I need to experience wellness, safety, community belonging, and happiness” while inner freedom is being in “a responsive relationship with everything that arises.” Inner freedom happens when you’re able to respond to internal and external stimuli instead of simply reacting uncontrollably. Secret freedom, the last ingredient, is understanding “the nature of things beyond duality, binaries, or labeling.”

These definitions of freedom are based on Buddhist concepts, but I don’t think you need to be a Buddhist to appreciate them. Ultimately, they’re about deconditioning and equity.

The New Saints is a guidebook for spiritual activists who want to redefine their goals and, with it, their playbook to get there. It offers a new take on exhausted concepts like prayer and forgiveness using a new definition of freedom. It offers new accessible meditation practices and ways to connect with the earth and the ancestors.

Featured image is All Saints Day I by Wassily Kandinski.

This newsletter is free for everyone. Want to support? Buy me a coffee via Venmo or PayPal.