Kai Cheng Thom’s most recent book, Falling Back in Love With Being Human, is a series of letters to people or groups of people who are hard to love. Which is everyone. She addresses trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) and trans women. She writes to sex workers and their clients. She has letters to mass shooters and their victims. She writes to J.K. Rowling. She writes to herself.

The current state of the world can make it awfully hard to ground ourselves in love. It can be hard to love ourselves when we represent something that society is raging against. And it’s just as hard to look at those doing the raging with compassion and curiosity.

In this newest episode of the podcast, I spoke to Kai Cheng about her book, what she learned from doing sex work in her twenties, and how she’s cultivating a spiritual practice grounded in love and recognizing the inherent worth of everyone. Basically: who is this wonderful person capable of writing love letters to those who hate her? And how did she become who she is?

Below, I’ve put together some thoughts about what it looks like to establish a love practice using highlights from her book and our interview.

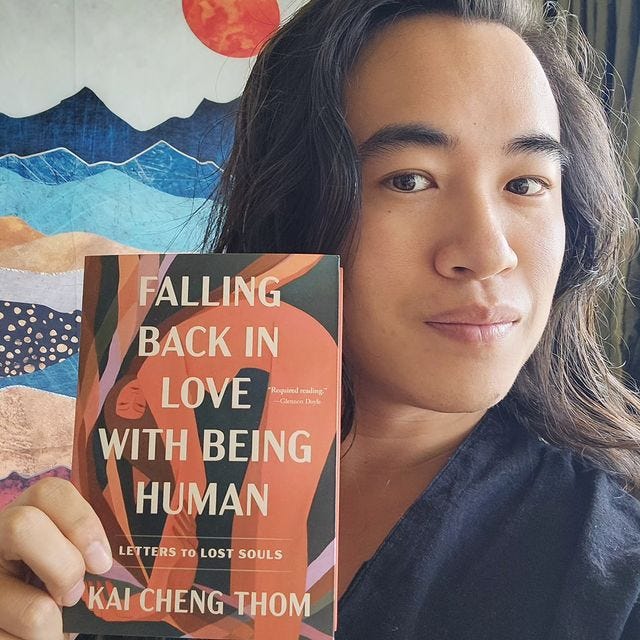

About Kai Cheng Thom

Kai Cheng Thom is an award-winning writer, performance artist, and community healer in Toronto. She was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and won the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Dayne Ogilvie Prize for LGBTQ2S+ Emerging Writers for her surrealist novel, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir. She is also the author of several other books, including a poetry collection, an essay collection, and two children’s picture books. Kai Cheng writes the advice column Ask Kai: Advice for the Apocalypse for Xtra. Find her on Twitter: @razorfemme or Instagram: @kaichengthom.

To Love Yourself: Claim Your Own Divinity

In her letter “to the sisterhood of trans femmes,” Kai Cheng writes that being a trans femme “is my plan, is my purpose, is not a mistake, is a gift from the First Femme, from the goddess, from the ancestor ghosts of sisters past and sisters to come; is a mission that i will not fail, that i will always fail, sisters, this i swear, no matter how many times i fail you i will always try again and again.”

There’s a lineage of divinity that trans femmes are connected to. But Kai Cheng also claims the divinity of trans femmes of color “comes from within.” Both are true.

She spoke to me about why the world is so terrified of trans femmes. And with all of the hatred that gets directed at them, “how could you not be the recipient of that and survive and somehow not be a divine glorious thing?” she asked.

Trans femmes aren’t the only people who can tap into a lineage of divinity. The aspects of our identity that are most at odds with how our society doles out power or privilege are often the most sacred aspects of who we are. They’re what connects us to something “greater than.” For instance, in our interview, Kai Cheng also spoke about the “double spiritual awakening” that many LGBTQIA2+ folks go through.

Of course, these aspects scare people. But they also give our lives and relationships deeper meaning.

I think we all know a part of learning to love ourselves is constantly working through cultural messages of hate. And a spiritual response to this hate is claiming one’s divinity. Not just seeing ourselves as worthy of love, but recognizing that we are indeed divine — whatever that means to you.

To Love Others: Peel The Onion

In our interview, Kai Cheng talked about how doing sex work taught her just how complicated people really are. She spoke about how seeing clients was like peeling the onion. The practice of sex work brings you closer to the core of someone than most other situations and in that sacred space, you see a tenderness to people that they don’t necessarily how in other environments.

In her letter “to the Johns,” which she reads in our episode, she writes:

i thought i knew about men before i became a whore. i knew stalking, i knew violence, i knew abandonment, i knew rape. i thought i might as well get paid for it. here’s what i didn’t know: that i could get paid to be treated like my attention was important. that an hour of my time was worth three hundred dollars or more. that my beauty, my body, my intelligence, my humor, my hands, could open one of you up and make you human again.

I asked her about how sex work taught her to see the best in men — their divinity.

On a very base level, what I learned was that men were human beings. I think I had actually really completely lost that. I was like, they're monsters! They're awful! And I was attracted to men, but I was like, it's like a curse. I'm attracted to these horrible demons. […] And to get to see another angle on men and so many more kinds of men just actually allowed me to understand that what I am attracted to in men is not this horrible demonic thing, but human beings. And I think this is where it loops back into falling in love with ourselves. I don't think that those of us who are attracted to men — I don't think that there is a way to resolve that inside ourselves until we acknowledge that what we are in love with is not something bad, that our love is not bad. And this is true for people, whoever you love. Our attractions are not sinful, are not harmful, are not dirty. There are harmful, shameful acts that can occur. But what we love is good and is beautiful, and that's what sex work did for me, which is pretty cool.

And for the cis men reading this —especially cis, straight, able-bodied white men — you’ve also internalized so much hatred aimed toward people you, especially now. As bearers of privilege, as maintainers of the patriarchy and white supremacy. How do you learn to love yourselves fully while acknowledging that which needs to change? I think the journey is similar.

There’s an overlap in Kai Cheng’s response to my question about learning to see the humanity and light in men and her letter to J.K. Rowling, where she exposes that Rowling is actually afraid of herself.

you wrote so many monsters, so many magical creatures, and yet you still don’t seem to know what a monster is, Joanne. a monster is a part of ourselves that we don’t want to find in the mirror. a part of ourselves we try to cut out and split off and put inside other people so that they can carry it for us: our fear. our shame.

What so often happens when we approach others with curiosity is we end up seeing a mirror. And the amount of compassion and grace we extend to others is returned to ourselves.

Dream Of Something Better For Everyone

In her letter to trans-exclusionary radical feminists, Kai Cheng writes, “dear radical feminist, hand on my heart, this i swear: i am not the end of your world. the world i dream of is big enough for both of us.”

This dreaming is at the heart of Kai Cheng’s compassion and, I believe, her faith.

“The route to finding love for something that one struggles with so much is faith,” Kai Cheng said in our interview. “Not faith in any particular religion necessarily, although some religions help, but faith in human beings, faith in ourselves, faith in the redeemable nature of the spirit.”

I find this response so profound. I think we often grow up being told what to have faith in. But what happens when we reimagine what faith is? What do we need to have faith in to survive; to heal; to foster the beloved community; to protect each other; to imagine something better?

When I asked Kai Cheng what it’s like to hold space for trans femmes and JK Rowling at the same time, she responded that “it simultaneously feels impossible and heartbreaking.” Her practice of doing this includes a stubborn optimism that things can get better. “I think we have to remember that faith says, actually, another world is possible, otherwise we would not be imagining it,” she said.

And her response makes me wonder if part of why it’s so hard to love certain people is because we’ve already given up on them.

How do we learn how to not give up on people? We have to keep imagining the impossible. And perhaps we need to have faith that we’re not doing this work alone.

Share this post